September 30, 2014 — This article discusses the faulty clinical practice of reusing contaminated syringes, needles and both multi- and single-dose vials of medicine.

This article also provides important recommendations for the prevention of diseases, including those caused by HIV and the hepatitis B and C viruses, associated with the improper administration of intravenous medications.

While this article discusses a specific incident that occurred between 2004 and 2007 in New York, its lessons, details, and root causes are like other, more recent instances of disease transmission.

A USA Today article published in 2012 quoted an infection disease specialist to say that, “The volume of poor (injection) practice is very large and unmonitored … It is, in some respects, a hidden epidemic … (and) the oversight is very weak.”

This USA Today article provided a federal statistic that since 2001, “more than 150,000 patients nationwide have been victims of unsafe injection practices, and two-thirds of those risky shots were administered in just the past four years,” according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Patient-to-Patient Disease Transmission

Recent breaches of infection-control protocol demonstrate the contribution of the improper use of syringes and multi-dose medicine vials to disease transmission.

In November 2007, health officials in New York advised 628 patients by certified mail to be tested for infection with HCV, the hepatitis B virus (HBV), and HIV.1-3

These patients were deemed to be at risk of infection because records indicate that each had received an injection from an anesthesiologist between January 1, 2000, and January 15, 2005.

Health officials concluded that during this five year period this anesthesiologist—known as “Doctor A”—injected these patients with medicines at odds with infection-control standards.1-6

Health officials reportedly knew since January 2005 that Doctor A’s practice of reusing syringes between 2000 and 2005 was “likely” responsible for at least one case of patient-to-patient transmission of HCV.1-8

Nevertheless, it was not until November, 2007 — 34 months later — that health officials notified these 628 patients of the risk of their exposure to HCV and other blood-borne pathogens. And, in December, 2007, health officials decided to inform 8,500 additional patients of Doctor A’s that they too may be at risk of HCV infection.9

HCV is the causative agent of a potentially fatal liver disease, and contact with the blood of an infected person, which can occur during the reuse of a syringe (or needle) and/or a contaminated multi-dose medicine vial, is ordinarily required for its transmission.

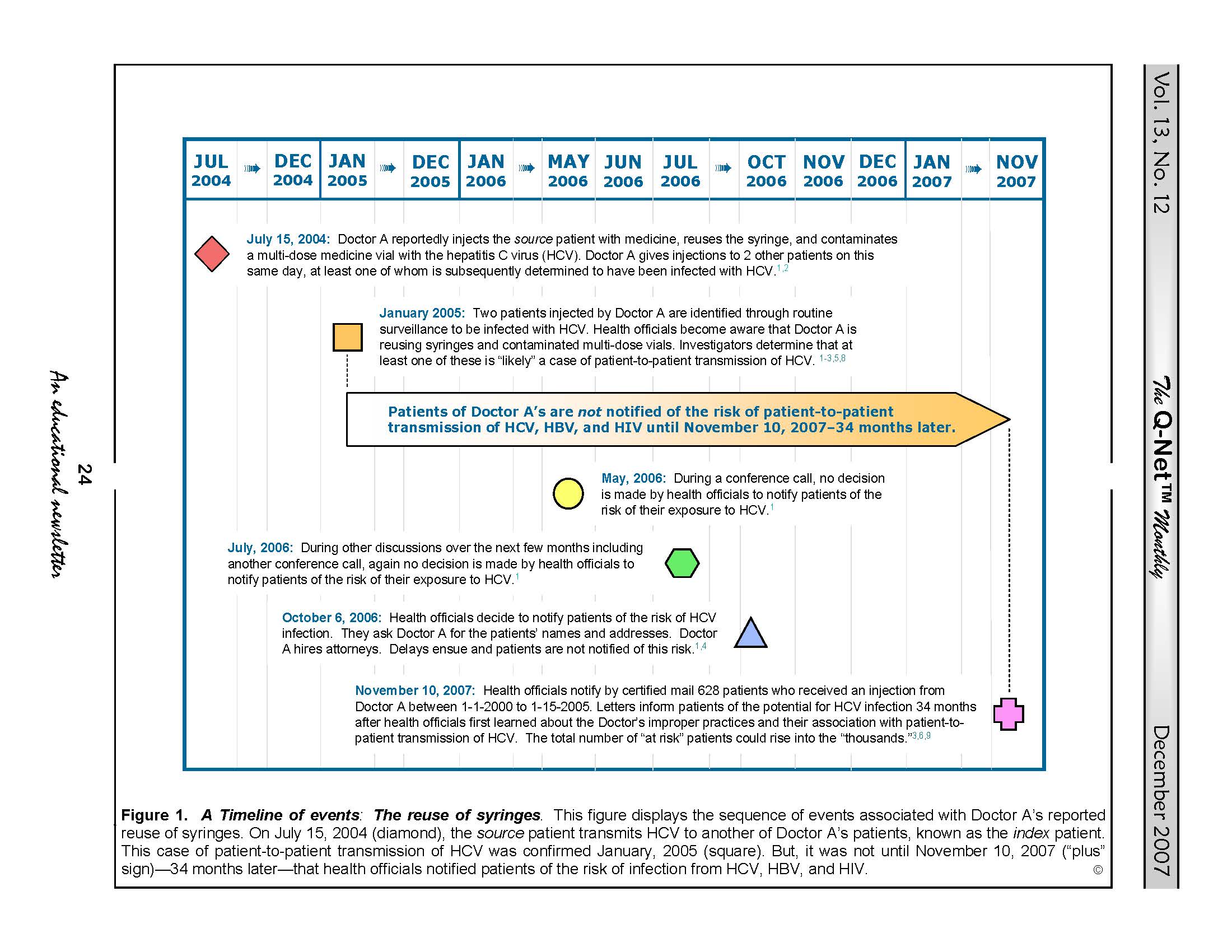

A timeline of this case’s relevant events is provided in Figure 1 located at the bottom of this article.

Other practices associated with the transmission of HCV include tattooing and unprotected sex. Prompt identification of all patients who may have been nosocomially infected with HCV is important to control and prevent its spread.

In the same 2012 USA Today article discussed above, a federal health official told the paper, “We’re trying to eliminate a range of harms in health care — high-level, complex challenges — and we look behind us and these basic, obvious, completely preventable problems are still occurring. … It really comes down to a matter of greed, ignorance or laziness.”

Quality, Safety and Case Reviews, Support: Click here to read about Dr. Muscarella’s quality and safety services designed to help clients identify the causes of healthcare-associated infections, including superbug outbreaks linked to contaminated duodenoscopes and other types of reusable medical equipment.

The Reuse of Syringes

This reported case of transmission of HCV in New York demonstrates that the pernicious practice of reusing syringes is not limited to under-developed countries, but can occur anywhere in the world, including the USA.

This case also underscores the importance of healthcare facilities ensuring that medical personnel fully understand that reusing syringes (and contaminated multi-dose medicine vials) is a risk factor for the transmission of HCV and other blood-borne pathogens.

Unlike single-dose medicine vials, which are labeled for use on one patient, multi-dose medicine vials are labeled, as their name suggests, for multiple uses on different patients. (That said, the improper practice of reusing single-use medicine vials can also pose an infection risk.)

Consequently, if single-dose medicine vials (if used properly and as labeled) virtually eliminate any risk of patient-to-patient disease transmission, multi-dose medicine vials can transmit HCV and other blood-borne pathogens from one patient to another if used improperly.

This same USA Today article quoted an advocate of safe infection practices to say, “People think, ‘This can’t happen in the United States; this is a Third World thing.’ Unfortunately, it happens on a regular basis, and it affects a lot of people, families, communities.”

For clarification, this report of patient-to-patient transmission of HCV in Long Island was not a result of Doctor A’s reuse of syringes (or needles) on different patients, as investigators may have initially suspected.

Rather, health officials attribute this case to the more subtle practice of reusing a syringe (with a new, sterile needle) to re-inject the same (infected) patient with additional doses of medicine drawn from a multi-dose vial.

The reuse of a syringe (contaminated with traces of infected blood) in this manner can contaminate the vial with blood-borne pathogens and, therefore, pose an increased risk of infection for any other patient subsequently receiving medicine from this now-infected vial.

According to health officials, a patient already infected with HCV and referred to as the “source” patient (i.e., the patient from whom the HCV originated3) received an injection from Doctor A on July 15, 2004 (see: Figure 1, below). This syringe was initially new and sterile but became reportedly contaminated with HCV when used to inject this (source) patient with a first dose of medicine drawn from a multi-dose vial.

Then, breaching infection-control protocol, Doctor A reportedly reused this same HCV-contaminated syringe (but with a new, sterile needle) to re-inject this same (“source”) patient with additional doses of different medicines drawn from other multi-dose vials—a practice that reportedly resulted in the inadvertent contamination of these multi-dose vials and their medicines with the source patient’s infectious HCV.1-6,8,10

And, it was the reuse of this contaminated multi-dose vial to inject with medicine other patients of Doctor A’s that “likely” transmitted the HCV horizontally from the “source” patient to at least one other patient, known as the “index” patient.

Doctor A reportedly is not the only physician who reuses syringes to re-dose patients with medicines from multi-dose vials.8 Although the use of multi-dose vials can be safe if proper infection-control measures are taken, the reuse of syringes is contraindicated.

Other cases of patient-to-patient transmission of the HCV

Other reports of patient-to-patient transmission of HCV similar in cause to Doctor A’s case have been published.

For example, a report published by the CDC in 2003 summarizes the investigation of four outbreaks of HCV and HBV in different healthcare settings.11 According to the CDC, each of these outbreaks was likely caused by the reuse of syringes and needles or the contamination of multi-dose medicine vials.11

An investigation of one of these outbreaks (Oklahoma, U.S.) concluded that a medical practitioner’s routine reuse of one syringe and needle to administer different intravenous (IV) medications to as many as 24 patients per day at a pain clinic was most likely responsible for the infection of 69 patients with HCV and 31 patients with HBV. (None of these patients were reported to be infected with HIV.11,12)

Other reports linking patient-to-patient transmission of HCV to contaminated multi-dose medicine vials also have been published.14-16 So, too, have reports of transmission of HCV from physicians and healthcare workers to patients.17-18

Recommendations

As this case of reusing syringes demonstrates, strict adherence to aseptic technique is necessary during the drawing of a medication for an injection.19,20

In view of Doctor A’s reuse of syringes and multi-dose medicine vials, review of the following recommendations is encouraged. These recommendations are applicable to GI endoscopy units and other healthcare settings where surgical, endoscopic, and/or pain management procedures are performed.

Specific recommendations that minimize the risk of infections during the preparation, handling, and intravenous administration of certain anesthetics are provided in a peer-reviewed article entitled “Infection control and its application to the administration of intravenous medications during gastrointestinal endoscopy” (Muscarella LF. Am J Infect Control 2004;32:282-6).19

1. ESTABLISH a quality assurance program that monitors medical staff members to ensure compliance with aseptic technique when filling syringes, using multi-dose medicine vials, and administrating injections (and IV medications).

2. USE a new, sterile syringe and needle (and IV tubing line) for each patient and for each entry into a source of medicine that was or may be used on more than one patient (e.g., a multi-dose medicine vial).

- DO NOT reuse any of these items — including the same syringe — to re-inject a patient from a source (a single- or multi-dose vial of medicine) that may be used on multiple patients.

- DISCARD all used syringes after each injection.

3. LABEL each pre-filled syringe properly. Include the medication’s name and the date and time the syringe was filled.

4. USE single-dose medicine vials. These vials are labeled for use on one patient.

- DO NOT reuse a partially-used single-dose vial to inject more than one patient with medicine.

5. WHEN USING a multi-dose vial, draw the medication with caution and in strict accordance with its labeling and aseptic technique.

- READ the labeling of each multi-dose medicine vial before its use. Discard the vial if contamination is suspected. As Doctor A’s infection-control breaches demonstrate, improper use of multi-dose vials (and the reuse of syringes to redose patients; see below) can result in patient-to-patient transmission of blood-borne pathogens.

- DO NOT pool medications from single or multi-dose vials into one vial for use on multiple patients.

6. NEVER reuse a syringe to redose a patient with (additional) medication from one or more multi-dose vials.

- ALWAYS use a new, sterile syringe (and needle) to inject a patient with additional doses of medicine — known as “redosing” — no matter whether drawing these doses of medicine from one multi-dose vial or from different multi-dose vials. The reuse of syringes is contraindicated.

FIGURE 1. A Timeline of Events. This figure displays the sequence of events associated with the investigation of Doctor A’s reuse of syringes. The pivotal events displayed in this figure begin on July 15, 2004, when Doctor A reportedly reused a syringe to re-dose the source patient with medicine, and end on November 10, 2007, when health officials notified these 628 patients of their risk of HCV infection. As previously mentioned, however, health officials reportedly first learned that Doctor A’s reuse of syringes was likely responsible for patient-to-patient transmission of HCV thirty-four months earlier in January, 2005. Whether this delay of almost 3 years prior to notifying patients of their risk of HCV infection was warranted is a matter of current debate. Responding to public criticism and reproof, health officials state that their thorough investigation of the facts of this case including its cause required almost three years to complete.4

REFERENCES

- Amon M, Ochs R. State: Key factors delayed patient notification. Newsday (Unknown date of publication; circa December 5, 2007)

- Whittle P. Hicksville man says doctor gave him ‘death sentence.’ Newsday November 15, 2007.

- State Health and Nassau County Departments notify patients of possible risk of hepatitis C exposure. Albany, NY. November 13, 2007.

- Amon M. Negotiation with L.I. doctor delayed notification. Newsday November 16, 2007.

- Amon M. Doctor faces Nassau DA probe in syringe case. Newsday November 21, 2007.

- Amon M. State says syringe probe patient list growing. Newsday November 23, 2007.

- Vitello P. A health dept.’s quandary: warn the public or supervise the doctor? New York Times November 17, 2007.

- Vitello P, Kershaw S. Patients were not told of misuse of syringes. New York Times November 16, 2007.

- Ochs R. State to ask more patients of Finkelstein to get tested. Newsday December 11, 2007.

- Amon M, Ochs R. Health Commissioner: We took too long to notify patients. Newsday November 27, 2007.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Transmission of Hepatitis B and C Viruses in Outpatient Settings — New York, Oklahoma, and Nebraska, 2000-2002. MMWR September 26, 2003; 52(38):901-6.

- Comstock RD, Mallonee S, Fox JL, Moolenaar RL, et al. A large nosocomial outbreak of hepatitis C and hepatitis B among patients receiving pain remediation treatments. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004 Jul;25(7):576-83.

- Bronowicki JP, Venard V, Botté C, Monhoven N, et al. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C virus during colonoscopy. N Engl J Med 1997 Jul 24;337(4):237-40.

- Germain JM, Carbonne A, Thiers V, Gros H, et al. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C virus through the use of multidose vials during general anesthesia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005 Sep;26(9):789-92.

- Krause G, Trepka MJ, Whisenhunt RS, Katz D, et al. Nosocomial transmission of hepatitis C virus associated with the use of multidose saline vials. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003 Feb;24(2):122-7.

- Tallis GF, Ryan GM, Lambert SB, Bowden DS, et al. Evidence of patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C virus through contaminated intravenous anaesthetic ampoules. J Viral Hepat 2003 May;10(3):234-9.

- Stark K, Hänel M, Berg T, Schreier E. Nosocomial transmission of hepatitis C virus from an anesthesiologist to three patients–epidemiologic and molecular evidence. Arch Virol 2006 May;151(5):1025-30.

- Lot F, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Thiers V, et al. Hepatitis C virus transmission from a healthcare worker to a patient.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007 Feb;28(2):227-9. - Muscarella LF. Infection control and its application to the administration of intravenous medications during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Infect Control 2004;32:282-6.

- Muscarella LF. Recommendations for preventing hepatitis C virus infection: analysis of a Brooklyn endoscopy clinic’s outbreak. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2001;22:669.

ARTICLE by: Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD of LFM Healthcare Solutions, LLC. Posted on December 28, 2012; updated 09/30/2014.