March 8, 2013 — A number of recent newspaper reports have highlighted the growing threat for patients in hospitals, long-term acute care facilities, and nursing homes of the increasing resistance to antibiotics of “superbugs” or “nightmare bacteria.”

Whereas the culprit most commonly affects chronically ill patients, there are growing concerns not only that it could also cause infections in community settings, but also may be transmitted, not just by the patient-to-patient route, but also via soil or water.

These newspaper reports include the following:

- “Mass. hospitals hit heavy by nightmarish supergerm — SouthCoast hospitals report zero cases” South Coast Today

- “‘Superbug’ stalked NIH hospital last year, killing six. The Washington Post

- “CDC says ‘nightmare bacteria’ a growing threat.” The Washington Post

- “Deadly Bacteria That Resist Strongest Drugs Are Spreading.” New York Times

- “Deadly ‘superbugs’ invade U.S. health care facilities. Deadly bacteria that defy drugs of last resort.” USA Today

- “CDC Warns Of Spread Of Deadly Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria.” CBS Miami

CDC’s assessment of an infection risk

Quoting an official of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), The Washington Post writes in its March 5, 2013, issue (see the link, above): “It’s not often that our scientists come to me and say we have a very serious problem and we need to sound an alarm. But that’s exactly what we are doing today.”

What are Enterobacteriaceae?

Enterobacteriaceae are a family of more than 70 species of bacteria, many of which reside in the normal bacterial flora of the digestive tract of humans (and other animals).

Examples of these bacteria include Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia (“E.”) coli, and species of the genera Serratia, Salmonella, Enterobacter, and Morganella.

According to news reports, a “superbug” outbreak of a deadly, drug-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae was responsible in 2011 and 2012 for 19 patient infections and 7 patient deaths at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Maryland.

What are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae?

Referred to my the CDC and press as “nightmare bacteria,” “superbugs,” and “super-germs,” carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, or CRE, are members of this family of bacteria that have developed a concerning resistance to a specific class of antibiotics known as carbapenems.

Carbapenems are a type of ß-lactam antibiotic that clinicians have used in the past as “last-resort,” or “last-defense,” antibiotics for treating patients infected with multidrug-resistant bacteria. Imipenem, ertapenem, and meropenem are examples of carbapenems.

Not only can CRE genetically transfer their antibiotic resistance to other bacteria within the same family — causing these other related bacteria, once sensitive but now superbugs, to be multdrug-resistant and to cause in patients potentially untreatable infections — but, when they infect the blood, CRE are also reportedly associated with a mortality rate of as high as 50%.

A highly transmissible gene (genes instruct the cell to produce proteins, which include enzymes) — an example is the “bla(KPC)” gene — is responsible for the bacterium to encode for (that is, produce) the carbapenemase enzyme that effects its havoc by physically dismantling and breaking down carbapenems. The production of carbapemases is a most important mechanism that causes CRE to be resistant to, and to confer ineffectiveness on, these carbapenems.

Examples of these CRE include carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (or, “CRKP”) and carbapenem-resistant E. coli.

For these reasons, an important type of CRE may also be referred to, therefore, as carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

CRE may become resistant to carbapenems through other mechanisms, too, however, not solely through their production of carbapenemase enzymes. But, no matter the mechanism, all types of CRE have public-health significance and warrant monitoring and attention.

According to the CDC, “Doctors, hospital leaders, and public health, must work together now to implement CDC’s ‘detect and protect’ strategy and stop these infections from spreading.” (Click here for more.)

A ‘detect and protect’ strategy is recommended by the CDC to stop infections of CRE from spreading.

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)

Carbapenemases are a type of β-lactamase enzyme, and they provide the bacterium that produce them with its resistance to carbapenems and other ß-lactam antibiotics by hydrolyzing (i.e., chemically dismantling) these antibiotics’ ß-lactam ring, which is a 4-membered molecular structure featured in every ß-lactam antibiotic.

K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (or, “KPC”) is one of a growing number of identified carbapenemase enzymes. Bacteria that produce KPC are a type of CRE (but not all CRE produce KPC).

K. pneumoniae that produce this KPC enzyme may be referred to as “KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae” — a strain of this resistant bacterium that was first reported in North Carolina, in 2001.

Through gene sharing, however, KPC production is not restricted to K. pneumoniae (as its name might belie). Bacteria other than K. pneumoniae — for example, E. coli — have now been confirmed also to produce the KPC enzyme and other carbapenemases.

CRE carry their genes for drug resistance on mobile elements, called plasmids, and readily share them with other microbes. When another bacterium, such as E. coli, encounters one of the plasmids, it can instantly become multi-drug resistant. [Read more.]

Carbapenemase enzyme production is not limited any longer only to Enterobacteriaceae, having also been identified in, for example, resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Still, many strains of Enterobacteriaceae, while “multi-drug resistant” (or, MDR), remain susceptible to carbapenems (and therefore are not CRE).

The NIH’s Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase is “the proverbial superbug that we’ve all worried about for a long time,” said an infection control specialist at the hospital (click here to read and important article about this outbreak in The Washington Post). K. pneumoniae can cause pneumonia and other types of infections.

Every enzyme is a protein, but not every protein is an enzyme. Similarly, every isolate of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (as noted by its name) is resistant to carbapenems, but not every isolate of K. pneumoniae (or of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae necessarily) produces the specific KPC enzyme, although production of KPC “is the most common mechanism of carbapenem resistance in the United States.”(1)

Click here to obtain a copy of the CDC’s “2012 CRE Toolkit – Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE).”

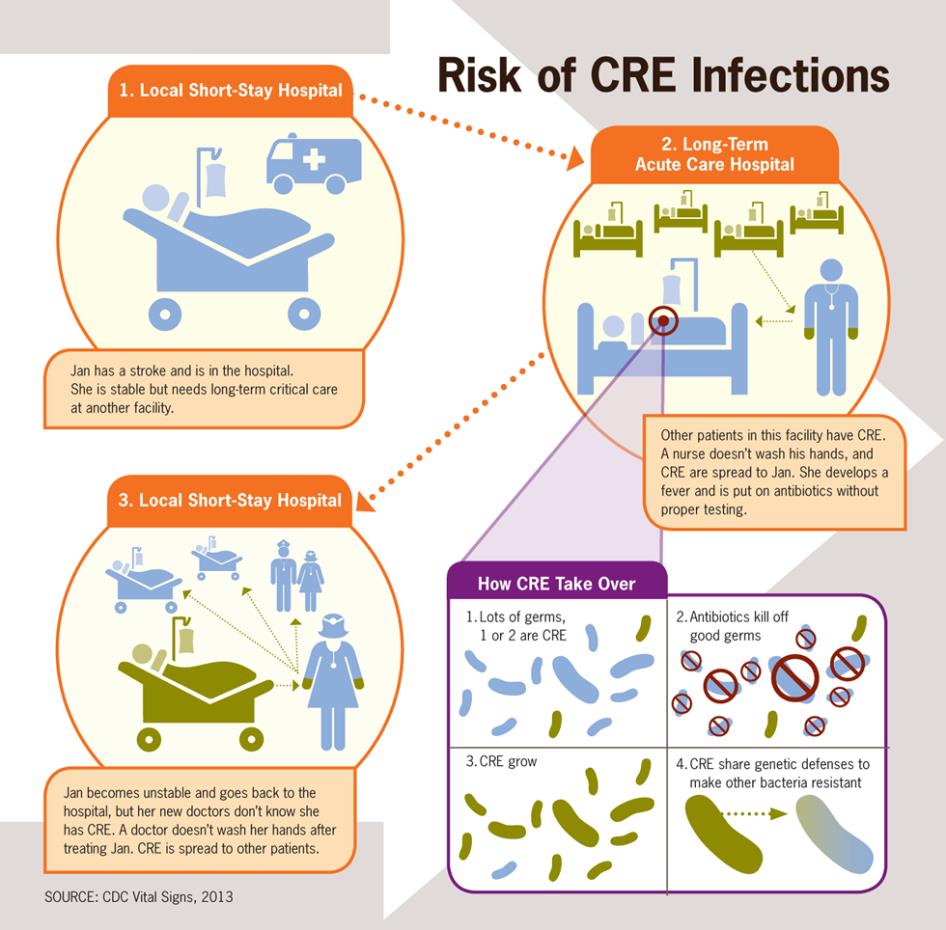

Mode of Transmission

CRE (and KPC) are transmitted from from one person to another via the direct-or-indirect contact route — for example, through the contaminated hands of doctors, nurses and other health-care professionals. CRE may be also transmitted via improperly cleaned and disinfected (or sterilized) reusable medical equipment, such as gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopes.

Click here to read Dr. Muscarella’s important series of articles on superbugs and the risk of their transmission during GI endoscopy.

Prevention

Like misidentifying a medical error’s true root cause and employing “off-the-mark” associated corrective actions, failure to properly identify a bacterium’s mode(s) of transmission — does the infectious agent spread by the airborne route or another route? — could result in the outbreak’s uninterrupted, un-controlled spread, with additional patient infections and injuries.

To prevent an outbreak, it is necessary to define the disease’s mode of transmission.

Because direct or indirect contact is CRE’s mode of transmission, implementation of Isolation Precautions — namely, not only of Standard Precautions but also of Contact Precautions — is indicated, if not typically required, to prevent CRE’s unabated spread throughout a healthcare facility.

Examples of Standard Precautions (which are universally practiced on every patient) include:

- proper hand washing (and hand hygiene)

- donning personal protective equipment (PEE)

- environmental cleaning, and

- employing safe injection practices.

Click here to read Dr. Muscarella’s blog “Isolation Precautions for the Prevention of the Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings.”

Examples of Contact Precautions (which are practiced in addition to Standard Precautions, as required,and only to prevent the transmission of diseases that spread via the “contact” route, as opposed to, for example, the airborne or large droplet route) include:

- the use of disposable, single-use (or patient-dedicated reusable) non-critical medical equipment (such as blood pressure cuffs and stethoscopes); and

- when possible, both:

- dedicating staff to the care of colonized or infected patients; and

- cohorting, or grouping together, infected patients (whenever isolating them in single-patient rooms is not feasible).

Closing remarks

According to the March 8, 2013, issue of the CDC’s MMWR publication, in the article “Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae” (click here): “Enterobacteriaceae are gram-negative bacteria … that can cause invasive disease but generally have been susceptible to a variety of antibiotics.”

While not every member of the Enterobacteriaceae family is CRE, every CRE, however, are Enterobacteriaceae that, virtually by definition, have become highly resistant to most, if not all, antibiotics (including, of course, carbapenems) through several mechanisms.

Indeed, some strains of CRE have been reported to be pan-resistant (i.e., resistant to all antibiotics).

Click here to read Dr. Muscarella’s “Dear CDC” blog that raises concerns about the validity of the CDC’s conclusions in a “Vital Signs” report in MMWR about trends in central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) during the past decade (are the CDC’s conclusions more political than scientific and evidence-based?). (Also read Dr. Muscarella’s peer-reviewed article on this topic by clicking here.)

Carbapenem resistance, while still relatively uncommon among Enterobacteriaceae, has increased during the past decade. According to this CDC report, the proportion of Enterobacteriaceae that were CRE increased from 1.2% in 2001 to 4.2% in 2011. This CDC report also found that “CRE bloodstream infections are associated with mortality rates approaching 50%,” as noted above.

Efforts to control CRE are crucial, but no more so than those measures designed to increase public awareness, the transparency of health care, and the integrity of infection control and public health. Evidence-based (not political) solutions are required to prevent disease transmission and to save patient lives.

Click here to read one health advocate’s article in Investors Business Daily (3-12-2013) entitled “CDC Should Stop Playing Politics With Disease Control.”

Without incentives that reward, not only healthcare personnel for identifying the root causes of disease transmission (as opposed to hiding these causes and the associated infections for fear of public backlash and being fired), but also health care facilities for openly acknowledging identified antibiotic-resistant infections and both accepting responsibility and being accountable for these outbreaks and their causative errors, trends toward:

- secrecy and a lack of disclosure;

- the public reporting of infection data that have not been validated for accuracy and completeness and may misrepresent actual trends in health care;

- poorer quality and infection control in health care; and

- an increased risk of patient harm …

will likely be observed and the norm.

According to the Washington Post, officials at the National Institutes of Health failed to disclose promptly to the public an outbreak of CRE, although these officials have subsequently agreed “to notify state and county officials of any potentially high-profile diseases or outbreaks, even those that do not pose an obvious public risk, county officials (recently) said. Click here to read more about this change in policy.

Also read the commentary in The Washington Post “NIH should have told public of superbug” by clicking here.

Reference: (1) Kitchel B, Sundin DR, Patel JB. Regional Dissemination of KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009 Oct;53(10):4511-13.

Article by: Lawrence F Muscarella PhD posted 3-8-2013; updated 5-16-2014, Rev B.