January 26, 2017 — The Philadelphia Inquirer reported last September that Philadelphia’s Penn Presbyterian Medical Center had diagnosed mycobacterial infections in three patients who had undergone cardiac surgery using a heater-cooler device.

This hospital is the first in Philadelphia (PA) — though the third in Pennsylvania the past year — to publicly link a heater-cooler device to mycobacterial infections in patients who underwent open-chest surgery.

Penn Presbyterian is part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which operates under the direction of PENN Medicine.

In response to these infections, PENN Medicine began mailing letters, dated Sept. 19, to several hundred at-risk surgical patients who may have been exposed to the mycobacteria.

According to this letter, Penn Presbyterian replaced all of heater-cooler devices manufactured by the company that has been the focus of several recent federal safety alerts (i.e., Sorin).

Each of these at-risk patients underwent a complex cardiac surgery at the hospital between October 1, 2013 and December 17, 2015 using a heater-cooler device, according to PENN Medicine’s letter.

Neither the Inquirer article nor Penn Presbyterian’s letter to patients identifies the cluster’s mycobacteria type. This patient letter refers to the cluster’s organism as being “slow-growing,” however, so it is likely M. chimaera.

The Inquirer reported that these three infections were identified just weeks earlier, and that each infected patient was recovering.

The Sorin 3T has been the subject of several mycobacterial outbreak investigations and FDA safety alerts. An article I published in November reviews the regulatory history of this and other heater-cooler models.

PENN Medicine’s patient letter emphasizes that the risk of contaminated heater-cooler devices causing a mycobacterial infection is a nationwide concern, and is not limited to one city or state.

Prior to the disclosure of Penn Presbyterian’s mycobacterial cluster, only two other hospitals in Pennsylvania — Wellspan York Hospital and Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center — had publicly linked a heater-cooler device, both in 2015, to mycobacterial infections in patients who had undergone complex cardiothoracic surgeries.

Quality and Safety Reviews: Click here to read about Dr. Muscarella’s quality and safety services committed to assisting hospitals reduce the risk of healthcare-associated infections, including mycobacterial outbreaks linked to contaminated heater-cooler devices. Brochures of his services are available by clicking here.

Quality and Safety Reviews: Click here to read about Dr. Muscarella’s quality and safety services committed to assisting hospitals reduce the risk of healthcare-associated infections, including mycobacterial outbreaks linked to contaminated heater-cooler devices. Brochures of his services are available by clicking here.

FDA panelist: Inform “at risk” patients

Penn Presbyterian’s Sept. 19, 2016 notification of hundreds of patients of their potential exposure to mycobacteria during open-chest surgery is consistent with the advice of some experts.

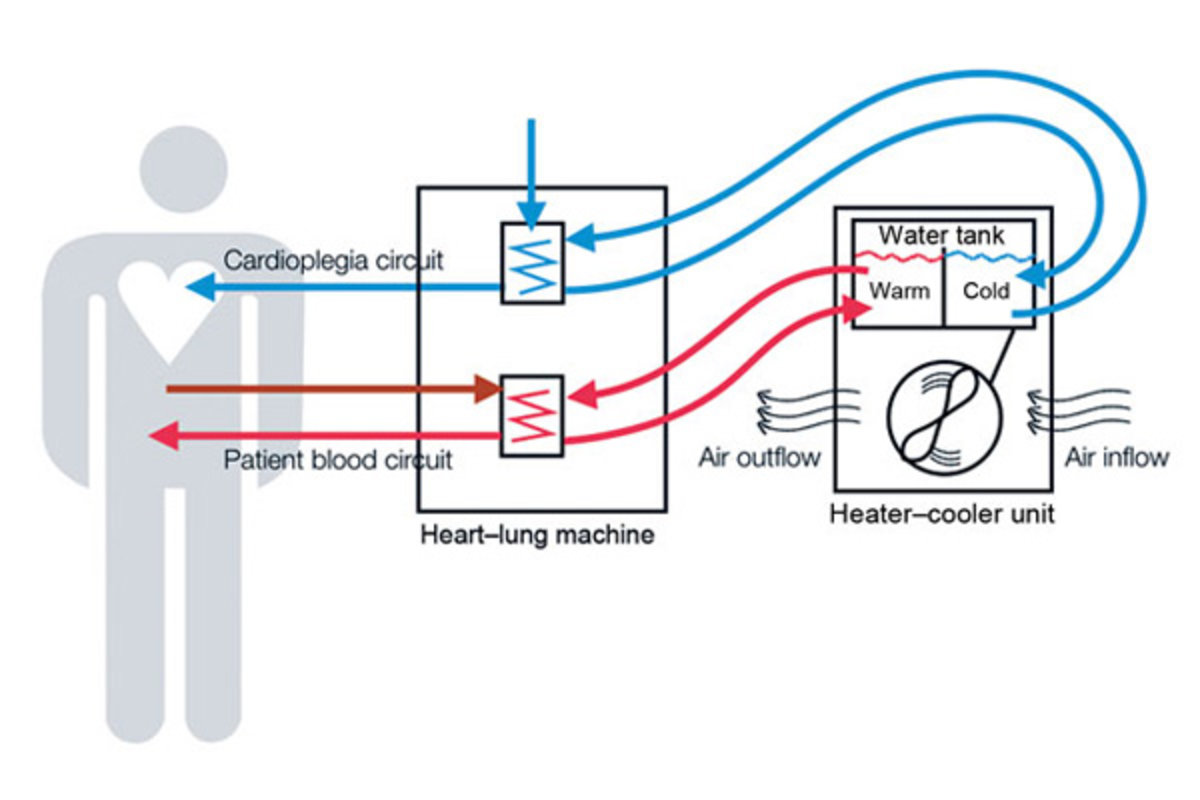

In early June the FDA hosted a 2-day advisory panel meeting to discuss the risk of heater-cooler devices becoming contaminated and infecting patients with mycobacteria.

Some experts told the FDA during this meeting, held on June 2-3, that identifying and tracking patients potentially infected by a contaminated heater-cooler device is a necessary step to better understand the true scope and risk of these infections.

During the meeting’s second day, an expert for the FDA suggested that hospitals should consider notifying all patients who have undergone cardiothoracic surgery using a heater-cooler device of the infection risk.

Dr. Laurence Givner, Professor of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC), told the FDA during this meeting that, “When we identify one case in a hospital, I think we need to (notify all) patients who had cardiothoracic surgery there with a heater-cooler device.”

As first reported by the York Dispatch three weeks ago, the Chief of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins Bayview (Baltimore, MD) agrees.

Dr. Jonathan Zenilman told the FDA during this 2-day panel meeting that one mycobacterial infection among patients who have undergone cardiopulmonary bypass surgery using a potentially contaminated heater-cooler device defines an “outbreak.”

This doctor compared some aspects of these mycobacterial infections to those of anthrax, telling the FDA that “one case of anthrax is an outbreak,” and that “in these settings you could make the case that one (mycobacterial infection among patients who had undergone cardiac surgery using a heater-cooler device) is an outbreak.”

Other experts disagree. Dr. Richard Hopkins, a congenital cardiac surgeon at Children’s Mercy Academic Medical Center (Kansas City, MO), told the FDA during this same June 2-3 panel meeting that he’s “a little loath to make a recommendation that’s going to cost a hospital a million and a half dollars based on one case.”

A representative from the Pennsylvania Department of Health told the FDA during this June 2-3 panel meeting that the estimated costs of a hospital notifying and testing patients for a mycobacterial infection, performing surveillance, and replacing contaminated heater-cooler devices with new equipment are $1.6 million. And this would not include the costs of litigation if a lawsuit were filed.

Another cluster of infections at a Philadelphia area hospital

Penn Presbyterian Medical Center is not the only hospital in the Philadelphia area in the past year that linked a cluster of mycobacterial infections to a heater-cooler device.

Another has also diagnosed mycobacterial infections in patients who had undergone cardiopulmonary bypass procedures using a heater-cooler device.

Four patients were infected with M. abscessus, two of whom expired, according to several regulatory reports I reviewed.

The hospital submitted four reports to the FDA a year ago linking these infections to the Terumo HX2 heater-cooler device, which competes with the more widely used Sorin 3T.

Terumo also filed four regulatory reports documenting four mycobacterial infections. In total, the eight reports were filed with the FDA between Dec. 2015 and Jan. 2016.

Each of these eight reports is discussed, in detail, in my related: “A Less Commonly Used Heater-Cooler Device Has Also Linked To Mycobacterial Infections.”

According to one of Terumo’s regulatory reports, two of the hospital’s doctors asserted that mycobacteria is in the Philadelphia and Delaware Valley water system, and that these organisms were “the likely cause” of this hospital’s infections, reasonably suggesting this hospital is in (or near) Philadelphia.

As is routine, the FDA redacted the hospital’s name from each of the filed regulatory reports.

Eighteen months earlier, in the summer of 2014, Greenville Memorial Hospital linked a deadly outbreak to a heater-cooler device contaminated with the same mycobacteria. This South Carolina hospital’s M. abscessus outbreak was the first in the U.S. to be linked publicly to a contaminated heater-cooler device.

The FDA’s oversight of heater-cooler devices is discussed in more detail in a related article, “Infections Are Not Limited to the LivaNova’s Sorin 3T Heater-Cooler or to M. chimaera.”

Article by: Lawrence F Muscarella, PhD. Posted: Jan. 18, 2017. LFM Healthcare Solutions, LLC Copyright 2017. LFM Healthcare Solutions, LLC. All rights reserved.

Lawrence F Muscarella PhD is the owner of LFM Healthcare Solutions, LLC, a Pennsylvania-based quality improvement and consulting company that provides safety services for hospitals, manufacturers and the public. Email Dr. Muscarella for more details.

E: Larry@LFM-HCS.com. Twitter: @MuskiePhD